I’m well (just had a brief fling with the flu). Montaigne reminds us that we die because we’re alive, not because we’re sick.

Lovely Ken,

Just finished Blue Plataea Part I on this quiet birdsong morning.

Roshi, good black dog, biggest radar ears on the planet,

tilts his head at the sound of

Pleiades in my cup

So many images to savor

thoughts to see

love to you dear Ken,

Nicole

Thank you for all your kindness and generosity through the years after my father died.

Thank you for your poetry. You bring his spirit back every time I read your poem.

____________________________________________________________

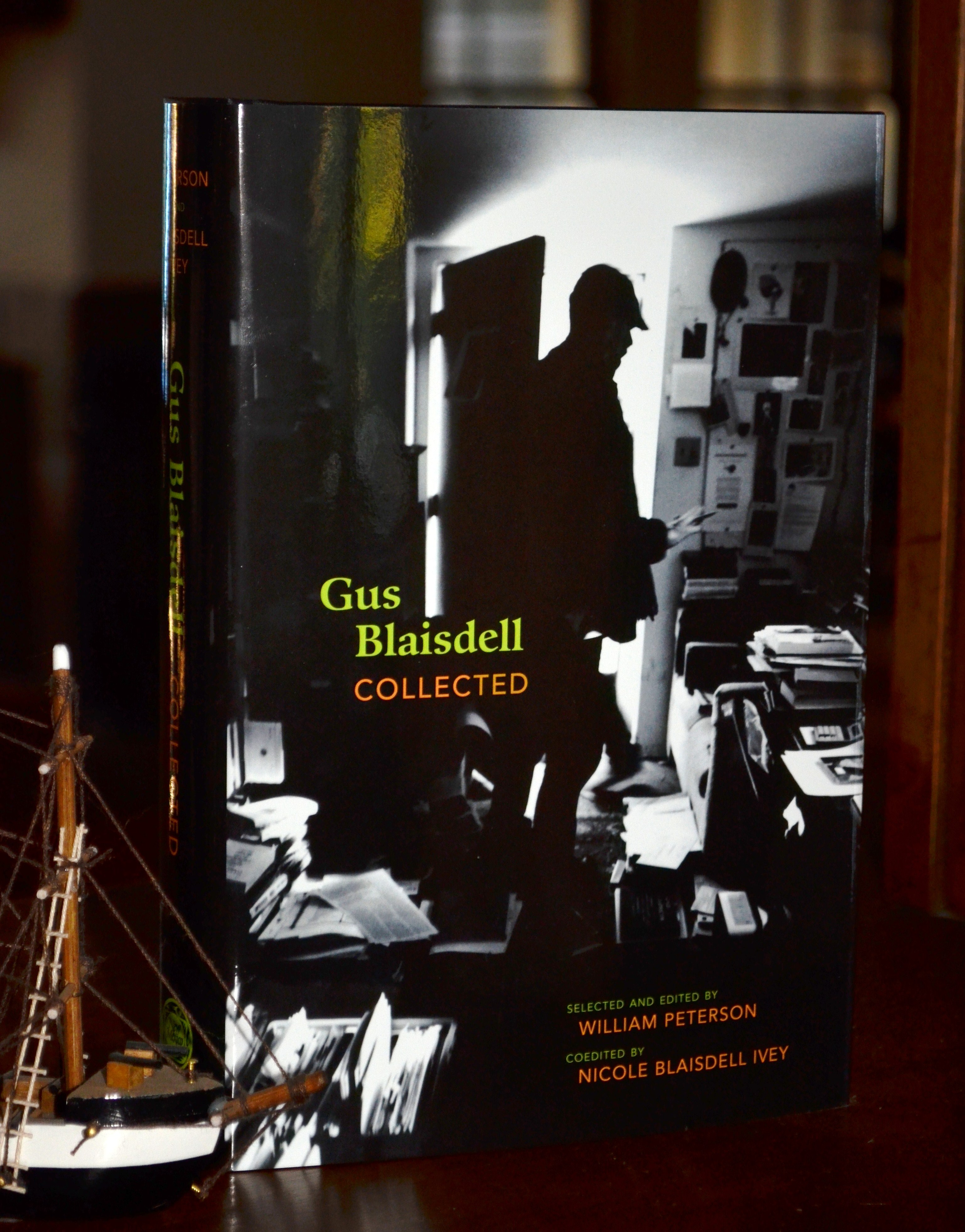

Gus

Albuquerque, NM

“Earth angel, earth angel, the one I adore”

–The Penguins

Ten months after your death I got the news.

All that time you were still alive. Each week

I thought of you or told a Blaisdell story,

The way I saw you first, at my front door,

Six hours late, the middle of the night, festooned

With leaves in your hair from the back yards you’d crashed through

As curly haired as Bacchus and as stoned:

“Your neighbors don’t know you, man”—you kept shouting,

“Professor Fields, goddamn it.” The next three days

We talked and drank around the clock, the only

Trace of that conviviality, the phrase

“Far fuckin’ out!” We said it a thousand times,

Late sixties eloquence, we never looked back.

We burned our lives to the rail, in a few years,

You sobered up and in a few more, me too.

From then on we remembered what we said.

You got to Stanford through a pachuco gang

In San Diego, tattoos on the backs of your fingers.

Arrested for stealing a book, you finished high school

In a bad boys joint run by the nuns. The bookseller

(Later your trade) thought about what you’d done—

He’d never had a thug steal Wallace Stevens,

So he sent you all the Stevens in his store

And In Defense of Reason, strange remorse.

This Winters is smart, you said. You came to Stanford

Where Uncle Lumpy, as you called him, loved you.

Your master and mine, he called you his wild boy.

One day the dean of men confronted you.

He’d just found out about your tattoos. “This school

Is a gentleman’s school, and I expect you to act

Like one, at least, and not come back next term.

We’ve never had anyone like you.” When you told Winters,

He stood up, pushing his chair into the wall,

And stumped across the quad. “I never knew

What he said to the dean.” Hell, you know what he said,

“This boy is ten times smarter than you. He stays”

You only taught the best: Mrs. Bridge,

Basho’s Narrow Road, Kurosawa,

Chris Marker and Descartes’ Meditations:

“Wrong in every one of them, but read them

Like a French New Novel, narrated by a man

Trying to keep from going mad, and failing.”

You were my only intellectual.

Your charm,

Your beautifully vulgar equanimity,

Brought learning to the table and the street,

“Where the rubber meets the chode,” I hear you laugh,

The rude road Strode rode. In that quick riff

You’d hear John Ford, Woody, and Sonny Rollins,

And the Duke holding court at The Frontier,

The all-night diner where you said good night.

When you described a round bed with a bedspread

Printed with a target—“it was like ground zero

At a fuckathon”—my wife fell in love with you,

“The funniest man alive.” And you still are.

“Not too many words between myself

And the world outside,” you wrote.

Well, more than you let on. A single room

Is overflowing with them, “Some white puff

Just beyond our mouth.” I want to phone you

When a doctor tells me of a patient complaining

Of fireballs in her universe, another

Suffering immaculate degeneration,

And a man controlling his rage by taking something

He called Hold Off. But no one’s home.

Gus,

Fireball, immaculate degenerate, you hold off,

You’re somewhere out there, as they say at Acoma

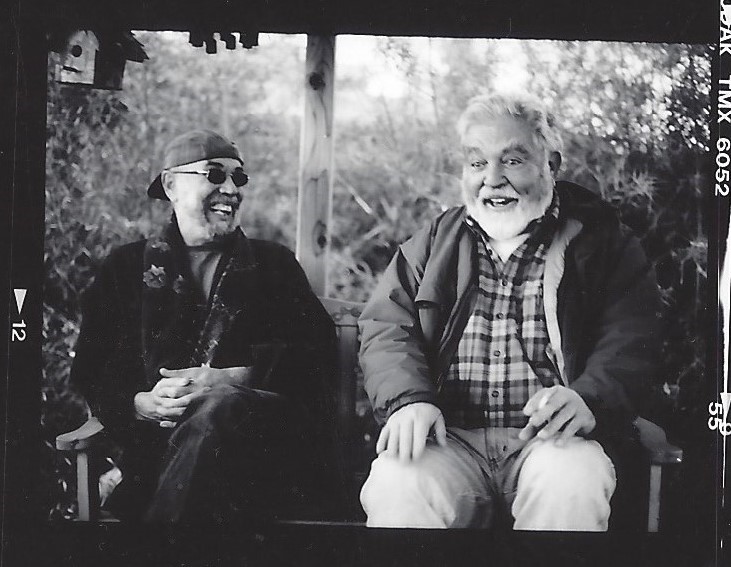

(Simon Ortiz recalls you at Okie Joe’s),

You’re somewhere out there, Gus, or as you’d say it,

(Corazon, baby) you are far fuckin’ out.

Ken Fields 2005

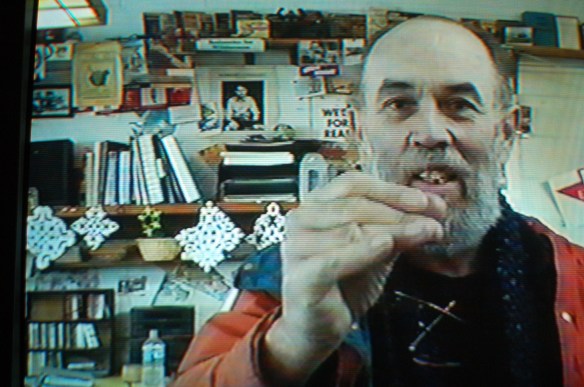

Blaisdell Ablaze

Gus Blaisdell 1935-2003

We talk about Terrence Malick in Heaven

It’s eight years since you left the world. The Tree

Of Life has come and gone. Birds fly

To creation, others to extinction, yet one

Trembles here

On this branch, now. Light and water

Burst forth in Texas—origin… there is no

Origin here—only music and Dante’s spirit

Guide, portal

Through which we infer eternity,

Our own making, a raft on fire

Refulgent on the thin film it rides upon,

Both gateway and end

Ken Fields – 2012

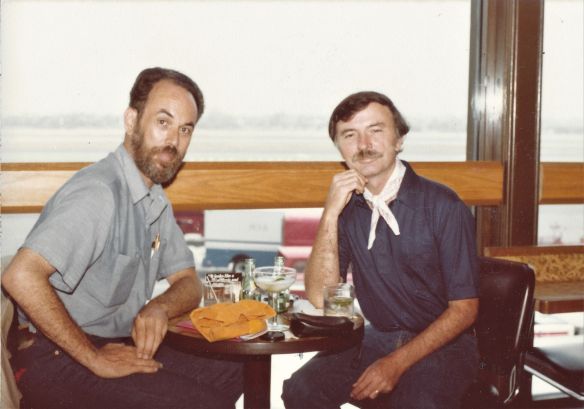

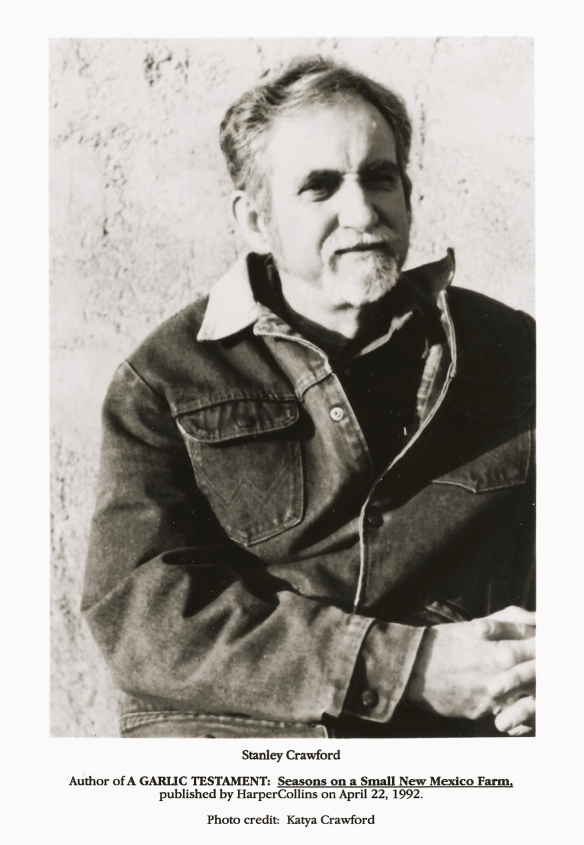

Kenneth Fields, longtime English professor and acclaimed poet, dies at 84

Known for his insight and wit, Fields was one of Stanford’s longest-serving faculty members. He taught for 53 years.

March 11, 2024

Kenneth Fields, professor of English and of creative writing, emeritus, in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and one of Stanford’s longest-serving faculty members, died Dec. 6 from complications of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. He was 84.

Fields earned his doctorate in English from Stanford in 1967 and joined the university’s faculty immediately afterward, retiring in 2020. During those decades, he published six poetry collections while teaching courses on creative writing, poetry, and film.

“He was one of the best raconteurs I have known,” said Tobias Wolff, the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor, Emeritus, and a former student, colleague, and friend of Fields. “When he finished telling a tale about old friends, family, university colleagues, or soldiers he’d served with, you felt as if you had shared a meal with them, or at least a drink.”

“In every breath could lie a poem”

While earning his undergraduate degree at the University of California, Santa Barbara, a poet introduced him to the work of Yvor Winters, a literary lion who was then teaching at Stanford.

Winters became an important mentor and colleague, and Fields became Winters’ student, collaborator, and even gardener. Fields described the experience in a Stanford Magazine story, writing that he would be working on a ladder when Winters would approach him, asking if he had read this or that poet.

“It was a great, if nerve-wracking, way to learn,” Fields wrote.

In 1964, Fields received a Wallace Stegner Fellowship for poetry from Stanford. The two-year creative writing fellowship for poets and fiction writers was transformative for Fields, altering the trajectory of his career. After he received his doctorate in English in 1967, he began teaching at Stanford that same year. He later co-led the Stegner program as a professor.

Fields’ teaching varied from the cornerstones of poetry, including French symbolist poets and beat poets, to various forms of storytelling including American Indian mythology, American short fiction, and Western film. He even taught a course on the 20th-century American jazz standards, popular songs, and show tunes commonly called the “Great American Songbook.” His lectures featured a loose, freewheeling style that incorporated his trademark wit and a river of knowledge that ran both deep and wide.

He published six volumes of poetry, praised for their erudition and humor: The Other Walker (Talisman Literary Research, 1971); Sunbelly (David R. Godine, 1973); Smoke (Knife River Press, 1975); The Odysseus Manuscripts (Elpenor Books, 1981); August Delights (Robert L. Barth, 2001); and Classic Rough News (The University of Chicago Press, 2005). At the time of his death, he had been working on Blue Plateau, a collection of nearly 1,000 poems.

In recent years, his work had earned such accolades as Poetry Northwest magazine’s Richard Hugo Prize, awarded for his 2009 poemOne Love.

“In his writing and his teaching, Ken always had a great sense of form and language,” said Seth Lerer, Fields’ longtime colleague at Stanford who is now dean emeritus of arts and humanities at the University of California, San Diego. “He knew that every line of poetry should be a human breath, and that in every breath could lie, potentially, a poem.”

Lifelong poet

Fields was born Aug. 1, 1939, in Colorado City, Texas. At just six weeks old, Fields moved to his new home, San Luis Obispo, California, with his family.

After a childhood spent bicycling the California coastline, Fields attended the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he became the first college graduate in his family. He followed this by serving in the U.S. Army from 1961 to 1963. He married his wife, Nora Cain, in 1979.

Music, relationships, and poetry itself were important to him and were common themes in his writing, as was his experience with Alcoholics Anonymous—he went into recovery in 1982, an experience he referenced in Classic Rough News.

Fields taught the Advanced Poetry Writing Workshop for the Stanford Fellows for many years,and he never stopped writing poetry. In 2020, he composed a tribute after the passing of his poet friend Eavan Boland, the former director of Stanford’s Creative Writing Program. “Loss is forever, but so is love,” Fields wrote.

Fields is survived by his wife; his daughters, Erika Fields Jurney, Samantha Fields, and Jessica Fields; grandsons Henry Jurney, Ed Jurney, and Charlie Jurney; and his brother Don Fields and sister-in-law Ginger Rutland.

By Paul L. Underwood

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/sfr/RCDDLSLSP5ATLJOCYLLTJ4YNCY.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/sfr/LQUXIXDIRJB3VATRMYP4SYV3BE.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/sfr/HNKOF4QGMRA25HACLUM6RS6KQU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/sfr/IHFHYWIQAVHHPGWES2SKPIZURY.jpeg)