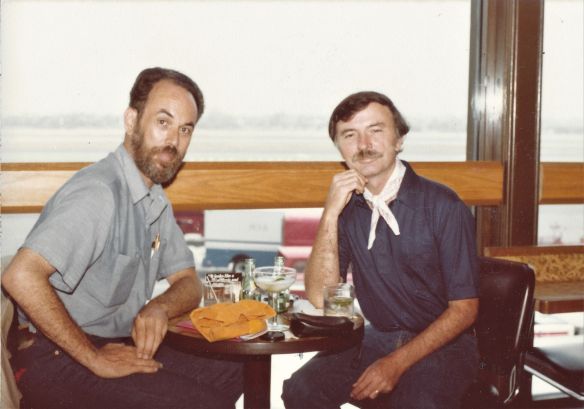

On a postcard from Lewis Baltz to Geoff Young:

Dear Geoff, Just returned from Paris to find your ‘O Hermie, O Augie’ (an edited collection of letters between Geoff and Gus) waiting for me. I’ve never properly mourned Gus because I’ve never really believed that he is dead. I’m perfectly prepared to accept the Death of God, even the Death of Art, but the Death of Gus is inconceivable. Hearing his voice–loud and clear–in ‘O Hermie’ reconfirms my belief that Gus is immortal and eternal.

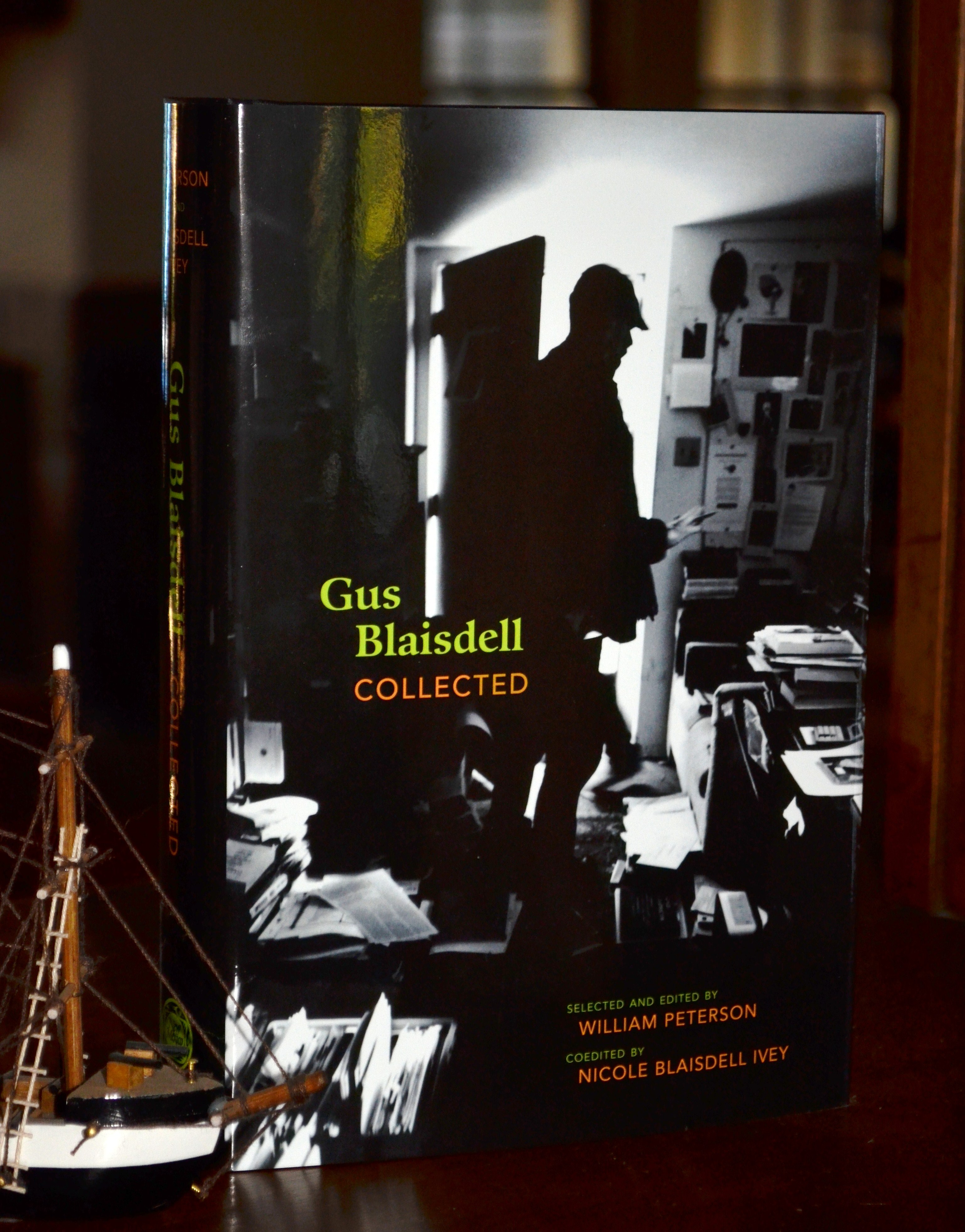

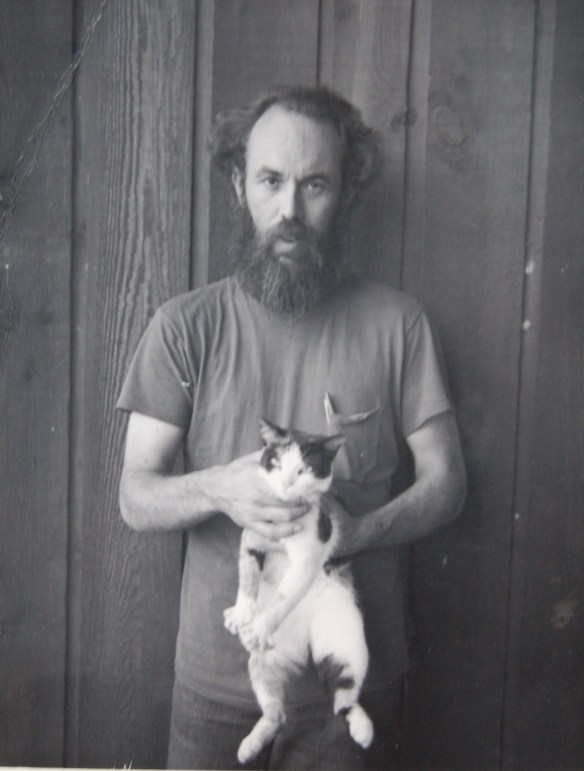

Below find an excerpt of Bldgs by Gus Blaisdell, his first essay on Lewis Baltz. Originally published in Three Photographic Visions, 1977. Republished in Gus Blaisdell Collected, University of New Mexico Press 2012.

Below find an excerpt of Bldgs by Gus Blaisdell, his first essay on Lewis Baltz. Originally published in Three Photographic Visions, 1977. Republished in Gus Blaisdell Collected, University of New Mexico Press 2012.

______________________________________________

Bldgs

I regret that I must begin in a quandary. But since I am in it and have been in it ever since I first began trying to think and write about Lewis Baltz’s photography over two years ago, this quandary is not only the place from which I must begin but it may also be the place in which, entangled, embroiled, and exasperated once again, I am forced to conclude.

Allow me to elaborate in a figure so that I may come to the various questions which will clearly indicate the ranges of my confusing (but not inchoate) concerns.

In the room in which I am presently writing this essay everything is concrete. That simple italicized phrase struck me the other morning with all the philosophical force of a secular revelation. And it persisted throughout the whole day, nagged during the conscious moments of a fitful night, and was still hauntingly present this morning when, in a mood of exasperation bordering on despondency, I once again sat down to yet another revision of my seemingly endless, as yet unfinished essay on the work of Lewis Baltz–my project a pile of notebooks, pages, file cards, jots and scribblings that has been with me nearly every day since that day in 1975 when I unexpectedly received in the mail a complimentary copy of The New Industrial Parks Near Irvine, California. As I leafed through the book it steadily dawned on me that Baltz was doing something in photography specifically and in art generally that had not been done before in either domain. His work stood forth as a summary limit and an extension, a point at which the promise in the work of others was engendered and fulfilled, and a point beyond which nobody else had gone. So strong was this conviction that it expressed itself paradoxically, that Lewis Baltz was a painter who had chosen photography instead of paint in which to make significant objects. The paradox here is not in the apparent restrictions consequent upon such a choice but in the media Baltz would be crossing and in the successful translations he would have to achieve. A painter who used photography–there was something of Japanese aesthetics in that, and in the restriction of means and the accepting of the automatisms that constitute photography, further limiting this medium to work in black and white fixed images.

Again, the above also had the philosophical force of worldly revelation and it has persisted, often annoyingly, throughout the years that have lead to the present writing in this room in which everything is concrete. Nothing here is abstract unless it is my mind or the meanings my written words may carry as my sentences achieve equilibrium. Everything in this room except mind and meaning is photographable, will yield an individuated aspect that can be fixed upon film. (The difficult “things in this room” that are not obviously individual and thus fixable are light, dark, and the shadows cast by the interruption of light by objects. None of these seem either trivially concrete or plainly abstract. Penumbral seems to be the accurate term here. And the penumbral is difficult for photography not only as object matter–what the camera points at out there–but also as subject matter, what gets fixed in the frame and shown in the print; and what takes its further meanings, beyond the frame and outside the print, from whatever network of knowledge happens to contain the print centrally and essentially like an idiom or a poem.)

The only conceivable thing in this room which might be wholly abstract in relation to every other photographable thing is a photograph by Lewis Baltz, Maryland 24, a photograph which is endlessly a reminder of this quandary in which I daily encounter my thought…