Saturday, February 22, 2014

a review of GUS BLAISDELL COLLECTED by George Kalamaras

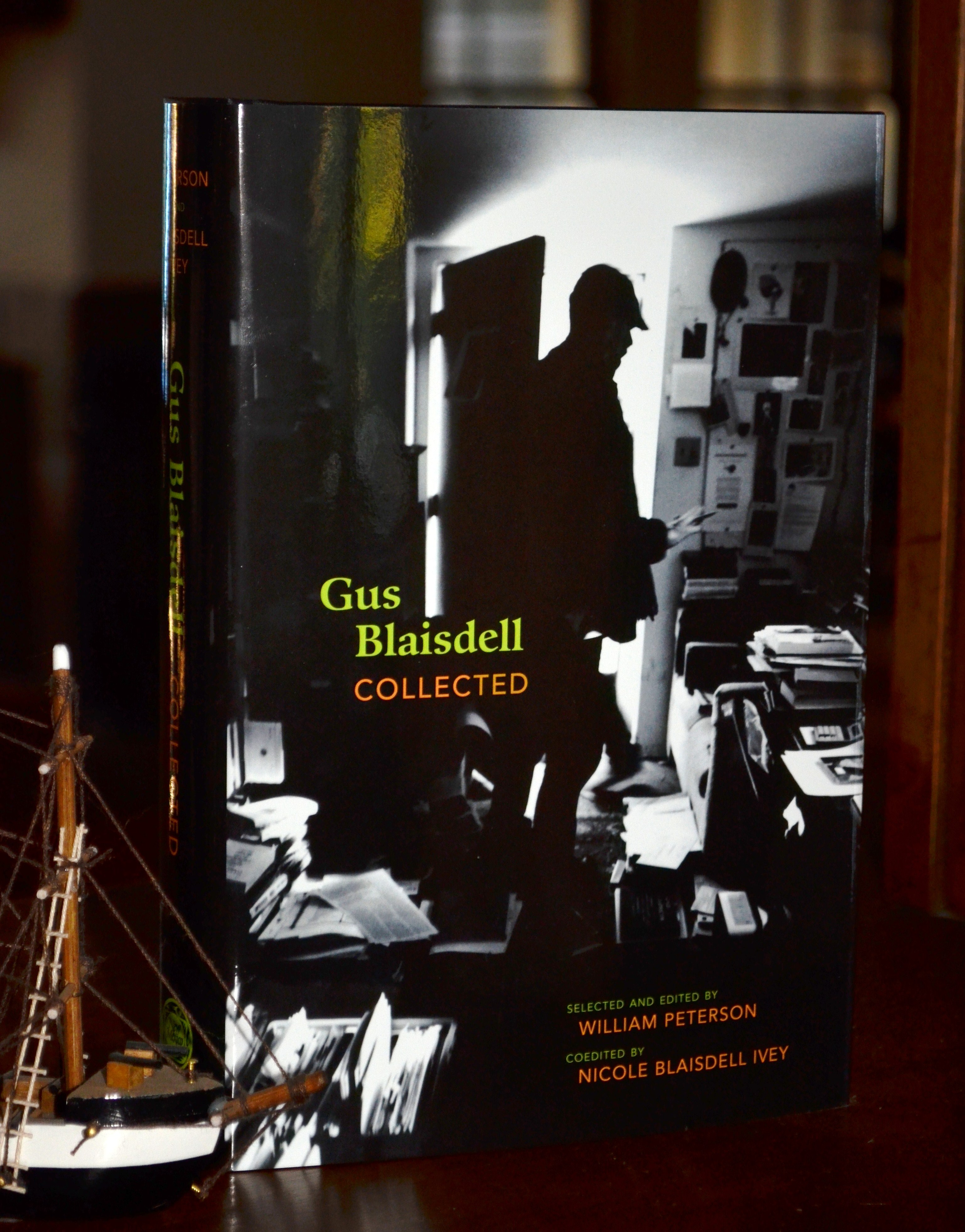

Gus Blaisdell Collected

Gus Blaisdell

Selected and Edited by William Peterson

Coedited by Nicole Blaisdell Ivey

University of New Mexico Press ($40.00)

by George Kalamaras

In the current land rush for the latest, hippest poetics, caught in the web of irony that so much contemporary poetry seems hell-bent to explore, much lineage that made current movements possible is ignored. This is particularly problematic when that lineage encompasses counter-movements and personalities that served as necessary ballast to keep the ship of the art of its time from sinking. Independent thinkers often suffer obscurity for the sake of their ideals. The battle plains of poetic history are littered with such figures, whilst the monocled generals, astride white steeds on the hill, wax profoundly about the philosophical consequences of their actions.

Publisher, poet, critic, bookstore owner, and provocateur, Gus Blaisdell (1935-2003), born Charles Augustus Blaisdell II in San Diego, was such a figure. Details of his life read like jazz improvisation—from enrollment at Brown Military Academy at age eight, to his fascination with all things Japanese after the close of the Second World War, to studying at Stanford with Yvor Winters in 1953, to living in Aspen and Denver (where he was a freelance reviewer of books and films for the Denver Post and worked with publisher Alan Swallow), to his correspondence with anthropologist Leland C. Wyman, leading to his readings on Navajo culture, shamanism, and religion and his 1964 move (with family) to Albuquerque to study anthropology at the University of New Mexico, to joining the staff at UNM Press the following year and coediting the New Mexico Quarterly, to enrolling in the doctoral program in mathematics at UNM in 1971, to publishing his poems with Howard McCord’s Tribal Press in the 1970s, to becoming owner of the Living Batch Bookstore in Albuquerque (where he also operated Living Batch Press, publishing Clark Coolidge, Gene Frumkin, Ronald Johnson, and Geoffrey Young, among others). He was friends with the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Ken Kesey, Robert Creeley, and Evan S. Connell. He and his fourth wife, Janet Maher, were married by Beat poet-turned-Zen-priest Phillip Whalen.

These events suggest a man with multiple, interrelated interests, and a brilliant, penetrating grasp of the significance of subversive art and a connection to indigenous knowledge. As his daughter Nicole Blaisdell Ivey writes in “A Chronology”:

Gus’s life was like jazz. The improvisation depended greatly on the depth of the cats he was playing with and the audience of the moment. Besides being a philosopher, poet, publisher, editor, essayist, critic, and teacher, Gus Blaisdell was a collector. He collected stamps, comics, autographs, ideas, experiences, quotes, books, music, art, and friends. And he took notes on all of them. . . . He thought of life (books, art, film, friends, wives, children) as moments and serendipitously interconnected pieces on his path from here to there. (339)

Some of these interconnected pieces—just some of what Blaisdell gathered—are brought together in Gus Blaisdell Collected, a generous (nearly 400-page) offering, fittingly from University of New Mexico Press. In addition to the remarkable “A Chronology” (forty pages of a fascinating gloss of a life—almost a mini-biography), Collected includes Blaisdell’s essays on a variety of topics, with section titles “On Photographs,” “On Movies,” “On Painting,” “On Reading and Writing,” “Fiction,” and “Shorts and Excerpts from Correspondence.” Blaisdell created and taught popular courses in cinema studies such as “Teen Rebels” and “Poetry and Radical Film” for almost twenty-five years at UNM, his contributions helping to establish a program and then a department in media arts. He also taught in the Department of Art and Art History. Individual essays are intriguing, a small sampling of which includes: “Space Begins Because We Look Away from Where We Are: Lewis Baltz’s Candlestick Point,” “’Obscenity in Thy Mother’s Milk’: John Gossage’s Hey Fuckface! Portfolio,” “Highlighting Hitchcock’s Vertigo with Magic Marker,” “Vatic Writing: Evan S. Connell’s Notes from a Bottle . . .,” and “Tell It Like It Is: The Experimental Traditionalists.”

Selected correspondence includes letters to Nicholas Brownrigg, Marcy Goodwin, Geoffrey Young, Lee F. Gerlach, and others. Of these, the correspondence with Brownrigg is the most fascinating; it begins in 1960 when Blaisdell was living in Aspen, and reaches into 1962 and 1963 when he was living in Denver. Just as a chronicle of the time it has value, but the complexities with which Blaisdell deals are engrossing. We see a young man caught in between this and that—distancing himself from the Beats and his earlier travels to Mexico and elsewhere, yet committed to his private luminosities, at the time not yet affixed to any particular tribe except the uncertain encampment of maturing yet still longing for the spiritual and psychic liberations of youth. He writes:

Your letters are far from obscure. And there is a good reason. Recall the circumstances under which our original correspondence began? Yes, Dharma Gus on the blistering Highways of America and in its cities and hotels and women. Shit, that is over. The adulation of idiocy (myself then and Jack Kerouac) is passé. We, you and I, have families and responsibilities and we have hopes that we ourselves frustrate only to incur misery. We love, as unashamedly as possible and with gritted teeth, knowing the pressure in our jaw is wrong. I am not saying there is a change in the elemental structure of our souls; I am saying there is a new form in which we exercise ourselves. (288)

Later, in his correspondence with Brownrigg, he movingly critiques universities: “The university—which strengthens the ego and unintentionally fucks up the instinctual—taught us the language of the tongue so thoroughly that, when we came to learn the natural language of bodies (two, coupled) we were made to feel perverse, clandestine, and rich. How much we have to unlearn day by day . . .” (295).

Despite the powerful inclusions of Blaisdell’s essays, letters, and fiction, there is a marked absence of his poetry. His greatest contributions may, indeed, end up being his essays on film and art, as well as his ability to gather a community around his publishing activities, including his noted reading series at the Living Batch Bookstore. Furthermore, selections of a writer’s life-work understandably need to draw parameters. However, Blaisdell’s ground of being—even when he corresponds, philosophizes, and critiques—is the sensibility of a poet, and the reader deserves more of a window into that part of what gets “collected” here.

That aside, Gus Blaisdell Collected is mandatory reading for anyone interested in the writing, film, and art of the period—and of an iconic figure in Albuquerque, in particular—as well as for those committed to valuing the contributions of independent thinkers who have helped make today’s freedoms of a daily practice of writing and art possible.